Kasato Maru – Japanese Overseas Migration Museum - JICA Yokohama

Kasato Maru

Japanese Overseas Migration Museum - JICA Yokohama

Not only do the Japanese have a high average life expectancy, but they also have some of the healthiest, most independent long-lived people in the world. Once could say that this longevity is backed by the Japanese diet, while takes advantage of the rich variety of ingredients found in the seas, mountains, and fields of Japan.

Over many years, human beings have adapted to the dietary environments of the regions where they live. Let’s take a look at how people have been affected by these dietary environments and the places they were born and brought up in.

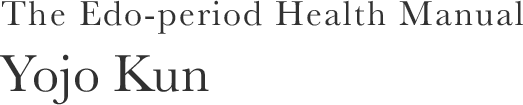

Compared to Caucasian people, Japanese people tend to develop hardening of the arteries later in life. However, it is reported that second-generation Japanese raised in Hawaii develop this condition earlier in life, and by the third generation, the difference to Caucasian people almost completely vanishes. Research into the rates of cancer development also show that from the second generation, there is a greater number of sufferers. It is speculated that this is because unlike their parents’ generation, the children and grandchildren of those immigrants have synchronized to the dietary lifestyles of where they live.

In the case of Americans of Japanese descent, cancer rates increased, and in Brazil, the switch to a meat-focused diet saw an increase in incidence of heart attacks, with statistics showing at least a 10-year drop in average life expectancy.

As there are multiple research reports showing that the adoption of Western dietary habits by immigrants of Japanese descent increases the rate of lifestyle diseases and shortens life expectancy, people have come to believe that Japanese diets are more healthy and lead to longer lives.

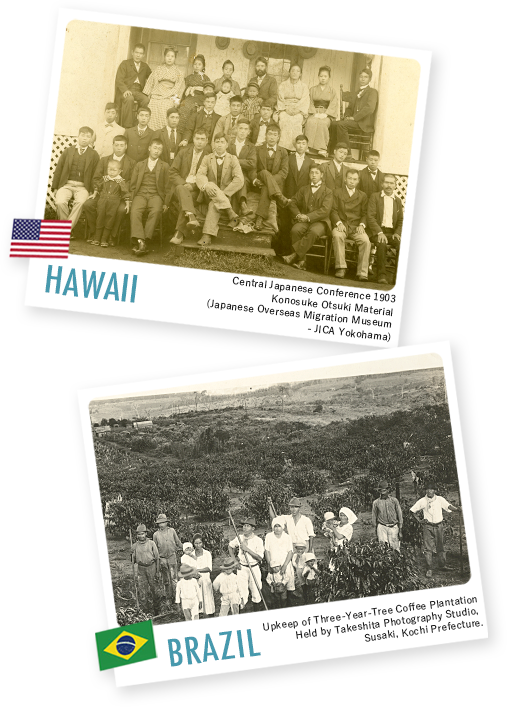

The mother’s milk of mammals contains lactose. Baby mammals break down this lactose into glucose and galactose to absorb it, using a catabolic enzyme called lactase. However, after the weaning period, they lose the ability to secrete lactase within the body, and become unable to break down lactose. This is why a considerable number of Japanese suffer effects such as diarrhea or upset stomachs as a result of drinking milk.

However, Europeans continue to be able to secrete lactase within the body even as adults. It is believed that their ancestors’ bodies adapted to living in cold environments where it was difficult to grow grains, which forced them to adopt a dietary lifestyle that depended on dairy products and meat to survive.

Proportion of adults incapable of digesting lactose among indigenous peoples of the Old World (excluding America)

One could say that human bodies adapt to the food of the region where they live, and continue to change as a result. Even European research to test the effects of the Mediterranean diet, well-known for its healthy qualities, has shown that there are differences in its effectiveness per country.

Source : The NU-AGE Project

Yojo Kun is a health manual

(a healthcare regimen) authored by the Confucian scholar Ekiken Kaibara during the Edo period (1603–1868). While the average life expectancy during this period was around 40 years old, Kaibara wrote the manual at the ripe old age of 83. To this day, Yojo Kun contains numerous messages that are still valid to this day, serving as a lifestyle manual that provides not only a healthcare regimen for the body, but also for the mind.

Yojo Kun edited by Kaibara Atsunobu – Oe Library

Tokyo Kasei Gakuin University

On Mental Health

“The first step to health is cultivation of one’s mind. Keep the heart from suffering and keep the spirit free from harm by being calm and peaceful, refraining from anger and greed, and restraining melancholy and worry—these are important methods to cultivating one’s mind.” (Volume 1, 9)

On Dietary Lifestyle

“In all meals, favor plain, lightly-flavored things. One must not eat many rich, fatty foods.” (Volume 3, 6); “Eating until one is full will cause bitter misfortune.” (Volume 3, 8); “By eating sufficient amounts of foods with each of the five flavors, one can avoid illness. Even if one eats a variety of meats or vegetables, continuing to eat the same things will cause those foods to stagnate in the body and inflict harm.” (Volume 3, 9)

Yojo Kun mentions “illness starts from the mouth,” “eating and drinking in moderation,” and “eating and drinking until eight-tenths full” (idiomatically, also eating and drinking in moderation) on numerous occasions when admonishing against overeating, making it clear that these are important principles. Modern dietary manuals also have their foundations in these principles.

On Gratitude for Food

“There are five thoughts when eating.” (Volume 3, 18)

- The five thoughts:

-

- ①Gratitude to the person who provided the food

- ②Thoughts for the labor of the people connected to the food

- ③Happiness at being able to eat something that tastes good, despite one’s own lack of aptitude, virtue, or outstanding actions or deeds

- ④Happiness at being able to eat enough, while others starve

- ⑤Thoughts for one’s ancient ancestors, who unable to grow staple crops, evaded starvation by eating fruits, berries, and roots

Portrait of Ekiken Kaibara (detail)

– Kaibara Family Archive

These five thoughts are present in the phrases itadakimasu (“I humbly receive”) and gochisosama desu (“It was a treat”), which the Japanese say before and after a meal respectively, and perhaps they will serve to help understand and pass on Japanese dietary culture.

* Source: Yojo Kun Zengendaigo-yaku (“Yojo Kun – Full Modern Language Translation”), as translated by Tomonobu Ito

The Japanese diet receives global attention, as it is seen as good for one’s health. There are various kinds of research taking place to examine what kinds of positive effects it has on the body.

Here, rather than looking at the nutritional value of the individual ingredients of the Japanese diet, we’ll be looking at the health benefits of the Japanese diet by evaluating diets in their entirety.

In the same way that Japan has the Japanese diet, other countries each have their own traditional diets. In an experiment to compare the Japanese and American diets using rats, it was found that the Japanese diet has the health benefits of energizing carbohydrate/lipid metabolisms, low stress on organs and low oxidative stress, and excretion of cholesterol. Because there was no conspicuous difference in PFC (protein, fat, and carbohydrates) balance between the Japanese and American diets, it is thought that the reason why Japanese diets had the above benefits may be due to qualitative differences, for example what kinds of ingredients were consumed.

- Rice

- Dried daikon strips and kombu with dressing

- Pork fried with ginger

- Miso soup

- Bread

- Pork and beans

- Salad

- Desert

- Coffee

- Cola

* The Japanese diet was based on the 1999 National Nutrition Survey, while the American diet was based on the 1996 USDA Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals. These were used as references to create breakfast, lunch, and dinner menus for a week each. The above shows part of the dinner menus.

While the Japanese diet has been inherited as a tradition, it has still changed as time passed. In an experiment to compare current and past Japanese diets using mice, it was found that the 1975 diet had the notable features of reducing the risk of obesity, fatty liver, and diabetes, as well as anti-aging and longevity-extending effects. There were no conspicuous differences in the nutritional composition for the diet from each period, so it is inferred that, like the comparison between Japanese and American diets, these features arise from qualitative differences.

When browsing with smartphone,this table can be side-scrolling.

| 1st Day | 2st Day | 3st Day | 4st Day | 5st Day | 6st Day | 7st Day | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Break fast |

Rice Salt-grilled salmon Natto Miso soup with Chinese cabbage and bean sprouts |

Raisin bun Omelet Sausage and cabbage sauté Fruit Milk |

Rice Dried horse mackerel komatsuna (Japanese mustard spinach) stew Scarlet runner bean amani (sweet pot) Miso soup with eggplant |

Toast Bacon and egg Fruit yogurt |

Rice Fried egg Natto Miso soup with cabbage and abura-age (deep-fried tofu) Fruit |

Toast Boiled egg Broccoli and tuna salad Fruit Milk |

Rice Asari clam and cabbage steamed with sake Natto Miso soup with tofu and abura-age |

| Lunch | Kitsune udon (udon soup with deep-fried tofu) Fruit |

Chinese fried rice Seaweed soup |

Yakisoba Fruit mitsumame (mixture of fruit, beans, etc. with syrup) |

Sweet potato rice Koya-dofu no fukumeni (freeze-dried tofu boiled in syrup) Pork miso soup |

Oyakodon (egg and chicken on rice) Kohaku namasu (red and white salad) Tsukudani |

Rice Eggplant fried with minced meat Simmered hijiki seaweed |

Sandwich Consommé soup Fruit |

| Dinner | Rice Niku-jaga (meat and potato stew) Vinegared mozuku seaweed Clear soup with cabbage and egg |

Rice Chikuzenni chicken stew Hiya-yakko (chilled tofu) Miso soup with spinach and abura-age |

Rice Creamed stew Boiled greens with Chinese cabbage and dried shrimp Cucumber and hijiki seaweed with dressing |

Rice Mackerel simmered in miso Soybeans boiled with diced vegetables Clear soup with Chinese cabbage and seaweed |

Rice Horse mackerel marinated in spicy sauce Miso dengaku (baked tofu) Clear soup with pumpkin and komatsuna |

Rice Flounder boiled with soy sauce and sugar Fried and simmered okara (tofu leftovers) Miso soup with taro and daikon |

Rice Sashimi Simmered satsuma-age fishcake and Chinese cabbage Shira-ae (vegetables dressed with tofu and white sesame) |

* Japanese menus, each for a week’s meals, were created to represent 2005, 1990, 1975, and 1960,

based on National Nutrition Surveys and other surveys of national health and nutrition.

One could say that this period was a time when the Japanese diet had started to Westernize slightly. Let’s take a look at five features of the 1975 Japanese diet, which had evolved to become the healthiest of the four diets chosen.

Diversity

Small amounts of various ingredients. At least three items of main and side dishes combined.

Preparation

Prioritization of simmered, steamed, and raw foods. Following these, boiled and roasted/broiled foods, then deep-fried and fried foods.

Ingredients

Strong intake of soy products, seafood, vegetables (including pickles), fruit, seaweed, mushrooms, and green tea. Moderate amounts of egg, dairy, and meat.

Seasonings

Careful use of dashi and fermented seasonings (soy sauce, miso, vinegar, mirin, sake) and limited intake of sugar and salt.

Format

Eating various foods based on the ichiju-sansai combination, with rice as the centerpiece.

- * Epidemiological research data (in the case of research on Japanese immigrants) and degree of influence on the genetic level

(“Comparison of Japanese and American Diets” and “Comparisons of Japanese Diets by Time Period”)

are quoted from research by Professor Tsuyoshi Tsuzuki, Associate Professor at Tohoku University Graduate School of Agricultural Science. - * In “Comparison of Japanese and American Diets” and “Comparisons of Japanese Diets by Time Period”,

rats/mice were fed freeze-dried, powdered food for three weeks, with analysis of gene expression levels. - * Gene expression: Protein, which constitutes the skin, bone, muscle, and organs of living things, is reconstructed into new material every day through metabolic activity. Gene expression refers to the creation of new proteins using DNA in the context of this activity.

“The Basics of Rice as a Food,” “Rice, the Heart of Japanese Food,” and “Rice Columns 1–3”

Born 1943. Chairwoman of the Japan Society of Home Economics – Division of Food Culture, and Director of Washoku Japan. Born in Gunma Prefecture. Graduated from Jissen Women's University, Faculty of Letters and Home Economics. Doctor of Food Science and Nutrition. Specialist in cuisine science and food culture theory.

“Why Japanese Food is Good for Health”

Born 1975. Associate Professor, Tohoku University Graduate School of Agricultural Science. Born in Toyota, Aichi Prefecture. Completed a doctoral degree at Tohoku University Graduate School of Agricultural Science. Assistant at Miyagi University School of Food, Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, then assistant professor before assuming current role in 2008. Specializes in the study of functional foods.