Since ancient times, the Japanese have actively accepted and introduced the cuisines of other countries, and have endeavored to refine them to suit the Japanese palate.

In the Heian Period (794 - 1185), Daikyo Ryori, which was introduced as a sort of court cuisine from China and Korean peninsula, became firmly established as the most formal banquet style for entertaining important guests in the Heian Court.

Further, in the Kamakura Period (1185 - 1333), thanks to the efforts of Buddhist monks who traveled to China to study, tea-drinking custom spread throughout Japan and Shojin Ryori, a form of vegetarian cuisine derived from the dietary restrictions of Buddhist monks, emerged and evolved in Buddhist temples. In this way, the earnest determination of our ancestors to learn about foreign culinary cultures has always been present in the shadows of the development of Japanese cuisine.

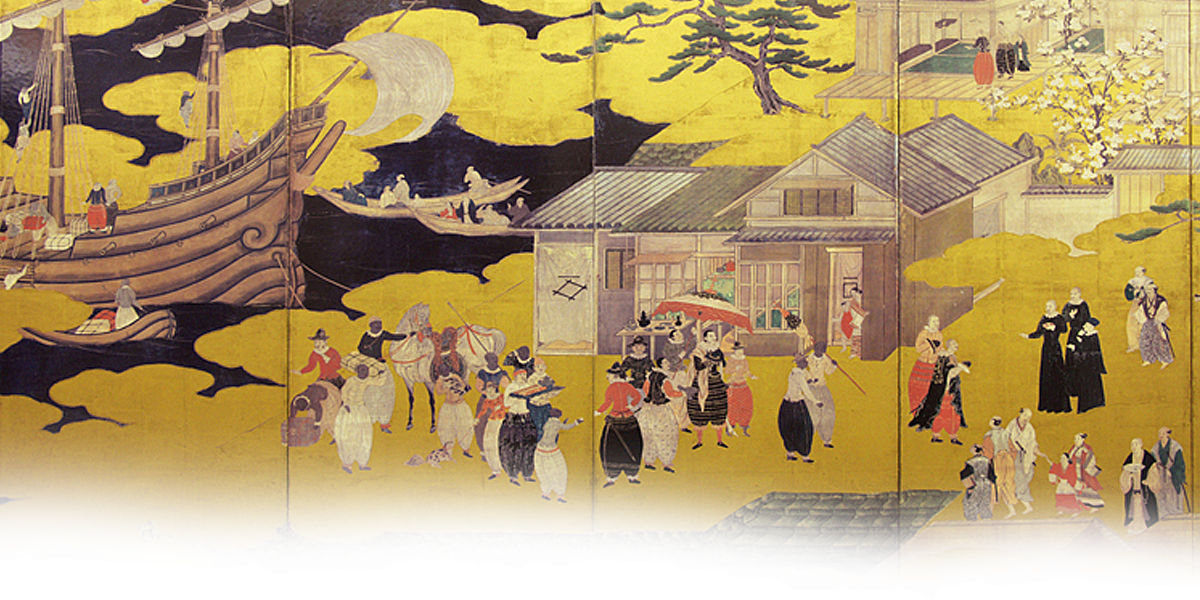

In the Muromachi (1336-1573) and Azuchi-Momoyama (1573-1603) Periods, with the arrival in Japan of Nanban-jin (Western Europeans), the Japanese encountered European cuisine for the first time. This included such foods as castella, a type of sponge cake originating in Portugal, bolo, a small round cookie also from Portugal, and tempura.

In the early Edo Period (1603-1868), when Japan entered a period of national isolation, the only connection with Western countries was through the Dutch trading post of Dejima in Nagasaki. Even so, the Japanese, in their intense curiosity, were very flexible in accepting the cuisine of the Dutch and Chinese who were permitted to live there, and enjoyed tasting foreign food culture by adapting them with Japanese ingredients and seasonings.

When Japan was finally opened to the rest of the world, it set about building a modern nation, seeking the model in the western lifestyles and ideas. Additionally, as exchanges with Westerners deepened, the number of western restaurants also increased.

Western seasonings and ingredients gradually permeated general society, and the trend of enjoying yoshoku, which is a distinctive cuisine arranged to suit the Japanese palate, became more and more prevalent.

What are the stories behind the birth of this yoshoku that many of us today feel so nostalgic about?

In this special feature, focusing on the period from the Edo Period to the Meiji (1868 – 1912) and Taisho (1912-1926) Periods, we will trace the history of our predecessors who boldly took on the challenge of accepting foreign cuisine cultures while repeating trial and error.