In the days when there were few places to eat out,

if people had to be away from their homes for long hours or when they were

traveling,

portable meals were common. In Japan, special containers were developed

to

make these portable meals easier to carry.

The foods were prepared in various ways and arranged in a way that

considered

the colors of the ingredients, with the added touches of seasonal

elements.

This evolved into a unique Japanese food culture, which is now so popular

that

the word “Bento” has become a well-known proper name overseas.

Here, we present Japan’s bento culture in various eras and scenes,

together with the characters that appear in those scenes.

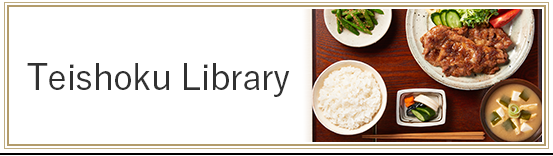

When leaving home to go to work, and when arriving at one’s destination, one needs bring food to keep from getting hungry. Bento originates from packed meals to eat outside.

The history of bento can be traced to the Nara period (710–784). Following the Taika Reforms of 645, centralized government had become established in Japan, and with it came the first national system for taxation—the soyocho system, a system of feudal dues (labor, goods, and produce as tax). Every province was required to pay taxes to the capital. The goods and produce that made up the taxes were brought to the capital by transporters known as unkyaku. These transporters were chosen from their settlements and brought the taxes for the whole community to the capital on foot. While the settlements prepared provisions for the transporters, it is estimated that combined weight of levied goods and personal provisions the transporters would have had been approximately 40 to 50 kg. The work of the transporters was harsh indeed, and their journeys were equally unforgiving.

As such, the provisions they brought with them had to be light and well preserved. The result of this need was hoshii—dried boiled rice. Hoshii could be restored with hot or cold water, but one could also eat it dry with some good chewing. Having already been cooked once, the starch of the rice would have been completely gelatinized, which made it easy to digest and kind to the stomach. It is said that hoshii can keep for approximately 20 years. Aside from hoshii, the transporters also carried salt, dried fish, and other such provisions. The “Nihon Shoki”, a chronicle of Japanese history compiled during the Nara period, also features a reference to “wrapping hoshii in cloth and arriving in Sakata”, giving an example of how people carried hoshii in this manner.

The techniques for growing rice in paddies arrived in Japan from the continent approximately 3,000 years ago. People gathered around rice paddies, forming settlements. The rice they were able to harvest became the core of their diet, and because it was possible to preserve it, rice became the foundation of the national economy, collected as tax.

While rice-growing has become increasingly mechanized in modern times, rice cultivation has traditionally been hard, physical labor since its beginnings. Whether it’s preparing a field, ploughing and irrigating, sowing the seeds, transplanting seedlings, weeding, harvesting, or threshing, there’s no end to the work. And it was bento that supported people through their daily work in the rice paddies, which lasted them from morning till night.

Usually, each worker would pack items like boiled barley rice and pickled plums into a container called a menpa, which was kept in a basket carried on their backs which also contained all their work tools. The word menpa originates from the word mentsu, which refers to a round wooden tub for carrying individual servings of rice, and some people think that this may in fact be the origin of the word bento.

For work like rice-planting, which needed to be done all at once in a short timeframe, the entire village would turn out to work together. This work was done together by large groups of people. During times like these, large pails packed with rice balls and side dishes for everyone, called “oke bento” (pail bento), would be brought out on a carrying pole. To bend over and plant rice is hard work, but it made the bento all the more delicious when everyone gathered at the ridges of the rice paddies to eat during breaks.

[“Illustrated Scroll of Seasonal Farming and Children at Play”] – Collection of the Institute for the Study of Japanese Folk Culture, Kanagawa University

This is an illustration of farm work through the year. One can see how, with the exception of particularly heavy work, the men and women would work together.

When planting rice, people would enter the paddies at around 6 in the morning, and finish at around 8 in the evening. Three meals were not enough to maintain their stamina, so between breakfast and lunch, and between lunch and dinner, they would eat light meals called kobiri. This word comes from kobiru, meaning a late-morning snack. These snacks consisted of bean-paste dumplings, rice cakes, simmered vegetables, and more...all made lovingly by the workers’ mothers. Each family had its own techniques and seasonings. Bento was not just to fill empty stomachs—it also strengthened the bonds between people from different families and areas as they ate together.

[“Picture Scroll of Farming”] - Mie Prefectural Museum

During the hot summer months, weeding was a difficult task, with people wearing bamboo hats to protect them from the sun as they went into the rice paddies. This illustration also shows people sitting on the ridges, their legs dangling down, as they eat bento.

Planting rice was also a religious activity. There have been traditions of venerating the gods of agriculture throughout the different regions since ancient times. It was said that the god of the mountains would come down to the village and become the god of the rice paddies once the spring cultivation season started, watching over the crop and bringing a bountiful harvest. The god of the rice paddies is called “Sa”. There are a lot of words related to rice-planting that begin with “sa”, indicating the religious aspect of the work, for example “Satsuki (May)”, the traditional month in which rice-planting took place, “sanae”, meaning rice sprouts, and “saotome”, meaning women who work the paddies.

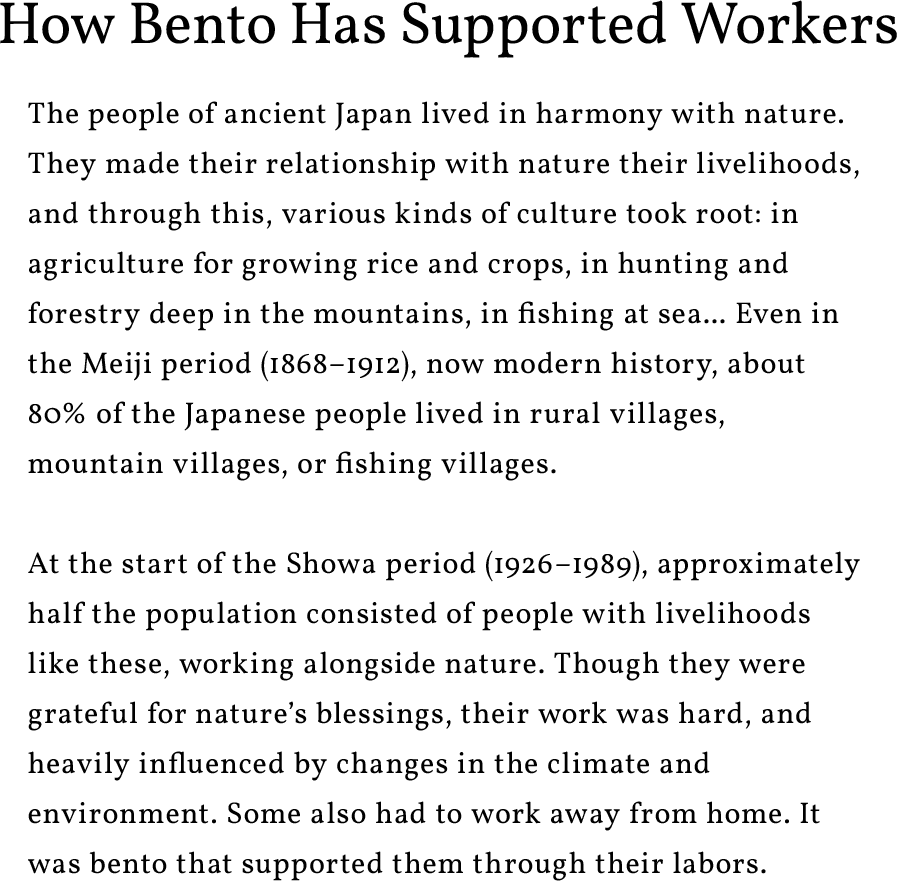

This is an eight-panel folding screen from the Muromachi period, which depicts the annual events that took place through the months of a single year, and the third and fourth screens illustrate the rice-planting process. The female workers (saotome) are lined up in matching garments, planting the seedlings. Planting rice was largely done by women. The people’s wishes for a good harvest were entrusted to those who would themselves bear children—the women.

In the upper part, you can see women putting bento into large pails and carrying them over. These women were called onari or hirumamochi (midday carriers), and they were sacred priestesses considered to be wives of the gods. Carrying cooked rice was the job of the onari. The pails carried by the men following them seem to be packed with food as well. The children, meanwhile, are having fun pitching in. Perhaps this is how they cultivated an interest in the work they would be responsible for as they got older.

– Tokyo National Museum collection

At the side, there are also people wearing masks and dancing while others play hand drums and taiko drums. This is dengaku, religious music and dancing. It is said that dengaku originated from singing and dancing in worship of the god of the rice paddy when planting rice, but some also say that it originates from rites to appease the spirits of the earth. Key features of dengaku are the lively music and humorous songs and dance, meant to encourage the hard work of the people carrying out the rice-planting. Dengaku eventually evolved into a performing art, and developed into noh theater and kyogen comedies.

In the lower part, you can see a man ploughing the rice paddy with an ox. Finally, at the feet of the dengaku performers, you can see a pail filled with sake, and sake bottles. Planting rice was hard work, so having such a wonderful feast to look forward to must have been some great encouragement. Bento really did support the people through their work.

(“Mount Fuji from the Mountains of Totomi”, from Katsushika Hokusai’s “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji”)

Approximately three-fourths of Japan’s total area is occupied by mountainous areas, and approximately 66% of the land is covered by forest. People have made a living in the mountains since ancient times, whether through hunting, slash-and-burn agriculture, cutting down trees, sawing lumber, or working wood. The workers who cut the wood were called soma, while those who sawed the lumber were called kobiki. Soma and kobiki worked in groups of 20 to 40 people, under the direction of their foremen. They would spend one to two months deep in the mountains, away from any settlements, and lived together in huts called soma-koya. When setting off for the mountains, they would bring with them a large quantity of provisions like rice, miso, salt, and salted fish, and once in the mountains, they would gather mountain vegetables, mushrooms, nuts and berries, and so on. As the woodcutting work progressed, their place of work went deeper into the mountains. There were many kinds of work other than woodcutting that took place in the mountains, such as hauling logs by sleigh, and building rafts in icy rivers.

– Photo provided by:Shibata Yoshinobu Shoten

in pickled mustard greens

There is a Japanese phrase: “a box of kobiki’s rice”. This refers to having done work that was so strenuous, you need a big meal to recover. Work in the mountains started before dawn. The workers would pack five go of rice into both the body and the lid of a magewappa rounded bento box, allowing them to bring two portions of bento, one for breakfast and one for lunch, with them. (One go is about three-quarters of a cup.)

Sometimes, they made rice balls to make it easier to eat the rice. Mehari-zushi, a feature of the Nanki and Kumano areas, consists of large barley rice balls wrapped in pickled mustard greens. These were made so that the people working in the mountains could quickly eat them during the short breaks in their busy work. “Mehari” sounds like “eyes wide open” in Japanese, and it is said that the name “mehari-zushi” originates from the idea that to take a bite out these large rice balls, you would have to open your mouth so wide that your eyes go wide open too. These hearty meals gave the workers the strength they needed.

– Takaoka Municipal Museum

The work of fishermen begins before dawn. Many fish are active and energetic before dawn and during the early morning. The fishermen start early so that they can bring in fresh fish that have only just been caught before the market opens. In the case of fishing with a fixed net, the net will be set up about 3 km offshore, and two boats will drive the fish towards the net, keeping them from escaping, while everyone else works together to bring up the net. With all this work to do, the fishermen will have no time to rest for a three-hour period in the early morning. After finishing the haul, it is finally time for breakfast. The fishermen’s breakfast comes in a pail-shaped bento box made from Japanese cypress. This is called “fune-bento”, “boat bento”, and it is kept in a net and carried like a bag. Each box contains seven go of rice, enough for one person (with one go being about three-quarters of a cup). The cypress box absorbs a good amount of moisture, helping it to preserve the deliciousness of the rice. These boxes have two levels—the first level holds the rice, while the second holds a flat bowl. The side dish for this bento is kabusu-jiru, a variant of miso soup made using some of the fish caught that day (“kabusu” means the fisherman’s share). The flat bowl is used to eat the soup, and after the fishermen finish eating, they put the rest of their share of the day’s catch into the bento box to bring it home to their families. The fishermen only carry rice as their bento, and the rest of their meal is prepared on the boats.

A fisherman’s meal and

a delicacy in its own right,

made with seasonal fish and miso

Danger is never far away from their work, and it is not uncommon for people to fall overboard in accidents during typhoons and storms. However, the boat bento boxes have a strong seal, and they can actually float and bob on the surface of the water, serving as a lifesaving tool. Additionally, if a boat takes on water, the bento pails can be used to bail out the water. These bento boxes are the result of the fishermen’s ingenuity. Though they go by different names from region to region, the boxes used at most fishing ports across Japan are generally the same.

EdoDuring the Edo period (1603–1868), the samurai would bring lunch boxes with them when they were going out on horseback or going hunting. When out riding, they would tie bento boxes to their waists that were designed to fit in snugly. These are called “koshi-bento”, meaning “waist bento”. Another name for them is “nogake-bento”, meaning “expedition bento”. They were designed not to fall off no matter how fast the horse ran, and they had a strong seal secured by a spiral-shaped, metal fitting on the lid used to screw it on. Meanwhile, lower-ranking samurai on duty would bring in a bento box carried on the waist of their hakama every day. As a result, koshi-bento also came to be associated with the comfortless image of lunch carried low-ranking workers. However, “koshi-bento” has always referred to homemade bento, and it was never the subject of ridicule.

– Photo provided by:Shibata Yoshinobu Shoten

It featured some surprisingly simple contents: shiitake mushrooms, dried gourd shavings, miso-preserved daikon, and rice balls.

In fact, during the Edo period, the daimyo would go to the inner keep of Edo Castle three times a month to attend the shogun, carrying bento. These visits were called “tsukinami onrei” (“monthly gratitude”), and the bento carried by the daimyo was called “go-tojo bento”, meaning “castle-visit bento”. Retainers were not allowed into the castle, so the daimyo would eat the bento they brought with them alone. The daimyo had a strictly defined order of attendance, and since all daimyo were vassals of the shogunate, they were not served tea and had to make their own. There was no brazier in the waiting chamber for fear of fire, even during the winter, and the daimyo were forbidden to engage in private discussion, so theirs was a rather lonely lunch time. And despite expectations, the daimyo’s bento had only simple and austere side dishes.

MeijiThe Meiji Restoration of 1868 brought an end to the age of the samurai, and a new age began.

The Meiji government, hoping to develop an independent state that could stand alongside the powerful foreign countries, promoted a policy of fukoku kyohei—enriching the country and strengthening the army. The four pillars of fukoku kyohei were tax reform, growing Japanese industry, developing the military system, and developing the academic system. To help cultivate modern industry, government-operated model factories were built, traffic and communications infrastructure was developed, and so on, giving people more places to work.

In 1872, the academic system was officially established, and through a number of reforms, such as making elementary school education compulsory, Japan’s education system was organized into a more modern state. With these changes, homemade bento carried by traveling workers and students had become almost ubiquitous. This was the start of the age of koshi-bento for everyone.

ShowaWith the period of high economic growth during the Showa period (1926–1989) came companies with cafeterias for their employees, and from the 1970s, fast food restaurants, family restaurants, and more opened one after another, increasing the range of lunchtime options available.

However, this did not mean the end of the idea that koshi-bento was always homemade. New products like frozen food or retort-pouch foods had been developed, and people were able to use these to create bento that was equal to what they could get eating at restaurants and cafeterias. Bento boxes also flourished with variety, with insulated boxes that were good at trapping heat or keeping food cool, boxes that featured fashionable designs, and more.

In the blink of an eye, more and more housewives came to see making bento as a kind of fun, and “aisai bento” (beloved wife bento) became a more common name than “koshi-bento”. Alongside this trend, homemade bento developed a softer, gentler image. Bento had become a bridge that connected the feelings of the people who made the food to the feelings of the people who ate it.

In Murasaki Shikibu’s The Tale of Genji, written during the Heian period (794–1185), the word “tonjiki” appears. The story describes how Genji’s coming-of-age banquet featured a number of tonjiki greater than that of the crown prince’s banquet, and how for his 40th birthday, 80 gu*1 of tonjiki were prepared. Tonjiki refers to egg-shaped rice balls made from kowameshi (steamed glutinous rice).

In Heian-period court feasts, tonjiki was prepared to serve the attendants waiting outside. These rice balls were large, with each one being slightly over one cup of rice (one and a half go), and because rice was mainly eaten in porridge form at the time, tonjiki was a rare delicacy. However, it was only the higher-ranking attendants who were served tonjiki.

Because tonjiki rice balls were compressed and stiffened by hand, they were very easy to carry, and in later times, tonjiki became a common form of rations for soldiers in times of war, as well as provisions for travelers. It was from the Edo period that these rice balls came to be called “onigiri”, and “omusubi,” another popular name for rice balls, dates back even further, to the language of court ladies of the imperial palace. It was from the middle of the Edo period that people began to wrap onigiri with seaweed.

*1 Gu means small tubs or containers.

*2 “oribitu” is a small container made of folded cypress panels, commonly used to hold items like confectionary or fish.

[“Illustrated Scroll of Annual Events – Ministerial Banquets”] – Tokyo National Museum collection

While the nobles enjoyed their feast, the servants waited outside the residence for the feast to finish. They were given tonjiki to eat.

Born in 1950. After working for Japan Airlines Co., Ltd. as a flight attendant on international routes, and later as a lecturer in the company’s cultural affairs department (providing instruction in serving customers), she established Human Education Service. Since 1997, she has worked as a special lecturer at the Japan Travel Bureau Foundation to improve hospitality in various fields of tourism and provide guidance on how to foster hospitality, and she has also served as a tourism promotion advisor and committee member for the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism, the Japan Tourism Agency, and local government. Since 2009, she has worked as a part-time lecturer at the Takasaki City University of Economics and other institutions. Her work involves research of modern hospitality, and as well as traditional Japanese hospitality and dietary culture.

![Scene of rice planting the Muromachi period (1336–1573) – “Tsukinami fuzoku byobu” [“Folding Screen of Monthly Customs”]](../../img/bento_library/column/column03/ttl-column03-04-pc.png)